Monday, October 31, 2005

Consecration: Thirteenth Day

St. Luke: Chapter 11:1-11

and

Prayers for Part 2

St. Louis de Montfort, pray for us!

St. Mary, pray for us!

Consecration: Part 2

Theme: Knowledge of Self

Prayers, examens, reflection, acts of renouncement of our own will, of contrition for our sins, of contempt of self, all performed at the feet of Mary, for it is from her that we hope for light to know ourselves. It is near her, that we shall be able to measure the abyss of our miseries without despairing. We should employ all our pious actions in asking for a knowledge of ourselves and contrition of our sins: and we should do this in a spirit of piety. During this period, we shall consider not so much the opposition that exists between the spirit of Jesus and ours, as the miserable and humiliating state to which our sins have reduced us. Moreover, the True Devotion being an easy, short, sure and perfect way to arrive at that union with our Lord, which is Christlike perfection, we shall enter seriously upon this way, strongly convinced of our misery and helplessness. But, how can we attain this without a knowledge of ourselves?

Prayers to be Recided During These Next Seven Days

(From the 13th day to the 19th day)

Litany of the Holy Ghost

(For private devotion only)

Lord, have mercy on us.

Christ, have mercy on us.

Lord, have mercy on us.

Father, all powerful, have mercy on us.

Jesus, Eternal Son of the Father, Redeemer of the world, save us.

Spirit of the Father and the son, boundless life of both, sanctify us.

Holy Trinity, hear us.

Holy Ghost, Who proceedest from the Father and the Son, enter our hearts.

Holy Ghost, Who are equal to the Father and the Son, enter our hearts.

Promise of God the Father, have mercy on us.

Ray of heavenly light, have mercy on us.

Author of all good, have mercy on us.

Source of heavenly water, have mercy on us.

Consuming fire, have mercy on us.

Ardent Charity, have mercy on us.

Spiritual unction, have mercy on us.

Spirit of wisdom and understanding, have mercy on us.

Spirit of counsel and fortitude, have mercy on us.

Spirit of knowledge and piety, have mercy on us.

Spirit of fear of the Lord, have mercy on us.

Spirit of grace and prayer, have mercy on us.

Spirit of peace and meakness, have mercy on us.

Spirit of modesty and innocence, have mercy on us.

Holy Ghost, the Comforter, have mercy on us.

Holy Ghost, the Sactifier, have mercy on us.

Holy Ghost, Who governest the Church, have mercy on us.

Gift of God, the Most High, have mercy on us.

Spirit Who fillest the universe, have mercy on us.

Spirit of the adoption of the children of God, have mercy on us.

Holy Ghost, inspire us with horror of sin.

Holy Ghost, shed Thy light in our souls.

Holy Ghost, engrave Thy law in our hearts.

Holy Ghost, inflame us with the flame of Thy Love.

Holy Ghost, open to us the treasures of Thy graces.

Holy Ghost, teach us pray well.

Holy Ghost, enlighten us with Thy heavenly inspirations.

Holy Ghost, lead us in the way of salvation.

Holy Ghost, grant us the only necessary knowledge.

Holy Ghost, inspire in us the practice of good.

Holy Ghost, grant us the merits of all virtues.

Holy Ghost, make us persevere in justice.

Holy Ghost, be Thou our everlasting reward.

Lamb of God, Who takest away the sins of the world, send us Thy Holy Ghost.

Lamb of God, Who takest away the sins of the world, pour down into our souls the gifts of the Holy Ghost.

Lamb of God, Who takest away the sins of the world, grant us the Spirit of wisdom and piety.

V/. Come, Holy Ghost! Fill the hearts of Thy faithful.

R/. And enkindle in them the fire of Thy Love.

Let us pray

Grant, O merciful Father, that Thy Divine Spirit enlighten, inflame and purify us, that He may penetrate us with His heavenly dew and make us fruitful in good works; through our Lord Jeus Christ, Thy Son, Who with Thee, in the unity of the Spirit, liveth and reigneth forever and ever. Amen.

Litany of the Blessed Virgin

Lord, have mercy on us.

Christ, have mercy on us.

Lord, have mercy on us.

Christ, graciously hear us.

God the Father of Heaven, have mercy on us.

God the Son, Redeemer of the world, have mercy on us.

God the Holy Ghost, have mercy on us.

Holy Trinity, one God, have mercy on us.

Holy Mother of God, pray for us.

Holy Virgin of virgins, pray for us.

Mother of Christ, pray for us.

Mother of divine grace, pray for us.

Mother most pure, pray for us.

Mother most chaste, pray for us.

Mother inviolate, pray for us.

Mother undefiled, pray for us.

Mother most amiable, pray for us.

Mother most admirable, pray for us.

Mother of good counsel, pray for us.

Mother of our Creator, pray for us.

Mother of our Savior, pray for us.

Virgin most prudent, pray for us.

Virgin most venerable, pray for us.

Virgin most renowned, pray for us.

Virgin most powerful, pray for us.

Virgin most merciful, pray for us.

Virgin most faithful, pray for us.

Mirror of justice, pray for us.

Seat of wisdom, pray for us.

Cause of our joy, pray for us.

Spiritual vessel, pray for us.

Vessel of honor, pray for us.

Singular vessel of devotion, pray for us.

Mystical rose, pray for us.

Tower of David, pray for us.

Tower of ivory, pray for us.

House of gold, pray for us.

Ark of the Covenant, pray for us.

Gate of Heaven, pray for us.

Morning star, pray for us.

Health of the sick, pray for us.

Refuge of sinners, pray for us.

Comforter of the afflicted, pray for us.

Help of Christians, pray for us.

Queen of angels, pray for us.

Queen of patriarchs, pray for us.

Queen of prophets, pray for us.

Queen of apostles, pray for us.

Queen of martyrs, pray for us.

Queen of confessors, pray for us.

Queen of virgins, pray for us.

Queen of all saints, pray for us.

Queen conceived without Original Sin, pray for us.

Queen assumed into Heaven, pray for us.

Queen of the most holy Rosary, pray for us.

Queen of peace, pray for us.

Lamb of God, who takes away the sins of the world, graciously hear us, O Lord.

Lamb of God, who takes away the sins of the world, have mercy on us.

V/. Pray for us, O Holy Mother of God,

R/. That we may be made worthy of the promises of Christ.

Let us pray

Grant, we beseech Thee, O Lord God, that we Thy Servants may enjoy perpetual health of mind and body and by the glorious intercession of the Blessed Mary, ever Virgin, be delivered from present sorrow and unjoy enternal happiness. Through Christ Our Lord.

Amen.

Ave Maris Stella

Hail, bright star of ocean,

God's own Mother blest,

Ever sinless Virgin,

Taking that sweet Ave

Which from Gabriel came,

Peace confirm within us,

Changing Eva's name.

Break the captives' fetters,

Light on blindness pour,

All our ills expelling,

Every bliss implore.

Show thyself a Mother;

My the Word Divine,

Born for us thy Infant,

Hear our prayers through thine.

Virgin all excelling,

Mildest of the mild,

Freed from guilt, preserve us,

Pure and undefiled.

Keep our life all spotless,

Make our way secure,

Till we find in Jesus

Joy forevermore.

Through the highest heaven

To the Almighty Three,

Father, Son, and Spirit,

One same glory be. Amen.

Sunday, October 30, 2005

Consecration: Twelfth Day

Imitation of Christ by Thomas a Kempis: Book 1, Chapter 25

and

Prayers for Part 1

St. Louis de Montfort, pray for us!

St. Mary, pray for us!

End Part 1

Saturday, October 29, 2005

Consecration: Eleventh Day

Imitation of Christ by Thomas a Kempis: Book 1, Chapter 25 (Of the Fervent Amendment of our whole life)

and

Prayers for Part 1

St. Louis de Montfort, pray for us!

St. Mary, pray for us!

Pre-Theology Ministry Log 02

Pre-Theologian Ministry Log

Date: Thursday, Oct 27, 2005

Event: St. Ambrose Family Outreach Center: Tutored the same lady studying for her G.E.D. that I tutored last time. Her name is Ms. Jenkins.

Name the feelings you experienced during the event: On the way to St. Ambrose, I was feeling very tired and was worried about how focused I would be once I got there. But once I started working with Ms. Jenkins again, her lively personality kept me engaged. This week we worked on reading and grammar. We got a lot of work done but also laughed and joked (as quietly as we could, not to disturb the others) throughout, as well. I really enjoyed helping her. She got a little frustrated at one point and asked me how what was reading had anything to do with what she would be doing in life. She explained that she had been doing social work and how proud she was of the work that she did. But how would reading decimals and combining simple sentences help her with that? I tried to encourage her by insisting that learning is good, in and of itself. By exercising her mind, she could expand the way she thinks and manages other parts of her social work. When she would read the directions to the exercises we were working on, I could tell she was just reading them one word at a time rather than forming complete sentences in her head. She exclaimed at one point that she had no idea what she just read and often times just skips the direction anyway and goes right to the problem. I told her to not be ashamed to read a paragraph or even a couple sentences and then stop and ask herself, “OK, what did I just read?” and then reread it. I told her I had to do that often myself, especially with philosophy (!). I encouraged her to check out a book from the library and practice reading in order to prepare herself for the essay portion of the G.E.D. I asked her what type of books she likes to read and told her I would check her out a book from our library if she could return it the next week. She said she’s never really read a book before but also mentioned she’s Catholic and finds the history of American slavery to be interesting. I felt happy to be able to bring her a book the next time we meet.

Other feelings: At one point we took a break and I joined Vic who was talking with the ladies at the front desk. They were discussing the young man that Vic is tutoring. They explained that he had gotten involved with drugs but now wants to get his education and “come to the Lord.” I like how she equated the two ( Vic began to describe briefly his faith, appropriate to the discussion, and the ladies expressed how happy they were to hear young men like ourselves publicly talk about their faith. They said so many men in their community think “Jesus is just for wimps.” She was very encouraging to us.

What was difficult and or troubling? Why? Ms. Jenkins wore a very revealing blouse which made me feel somewhat uncomfortable. One slightly troubling incident also occurred when I was talking with her about reading. Seemingly out of nowhere she said “When I was in prison… I read all the time!” It caught me off guard and I hoped I didn’t betray a shocked expression on my face!... I don’t think I did.

Where was God in this event? In the Sister working with the G.E.D. students, of course, and in other moments: When Ms. Jenkins told me she was Catholic, in the joy and productivity of our time together, in the understanding I was able to show for her difficulties, and in the ladies at the front desk who were passionate about the Lord and thankful for our witness (Vic and I).

What have you learned about yourself in the wake of this event? I’m more patient with others than I am with myself.

Mary, Model of Faith

Mary, Model of Faith

by Leon J. Suprenant, Jr

One of the many hallmarks of John Paul II's papacy was his consecration to the Blessed Virgin Mary, as represented by his papal motto "Totus tuus" ("All yours, Mary").

"Let It Be Done to Me According to Your Word"

His deep devotion to Our Lady is reflected in his magnificent 1986 encyclical Redemptoris Mater (Mother of the Redeemer), which provided us with a profound meditation on Mary in the mystery of Christ and His Church. More recently, he gave us his 2002 apostolic letter Rosarium Virginis Mariae (Rosary of the Virgin Mary), which introduced the new Luminous Mysteries of the rosary and called for a "Year of the Rosary."

Pope John Paul II also reminded us that Mary "is proposed to all believers as the model of faith which is put into practice." Perhaps at the close of this month specially devoted to Our Lady, we can allow Mary's faith to provide practical insights on how we can live out our faith. As the pope said, the faithful not only venerate and invoke Mary, "but also seek in her faith support for their own" (Redemptoris Mater, no 27). Let's use St. Luke's Gospel as our guide for making Mary's faith our own.

Our faith must be obedient. The obedience of faith must be given to God as He reveals Himself, and involves a complete submission of one's self to God. At the Annunciation, Mary's fiat ("let it be done," Lk 1:38) demonstrates her complete obedience to God and to His will for her. In fact it was by means of her fiat, her obedient faith, that "the mystery of the Incarnation was accomplished" in accordance with God's plan (Redempotoris Mater, no. 13). Vatican II highlighted the importance of Mary's "obedient faith":

Rightly, therefore, the Fathers see Mary not merely as passively engaged by God, but as freely cooperating in the work of man's salvation through faith and obedience. For, as St. Irenaeus says, she "being obedient, became the cause of salvation for herself and for the whole human race." Hence not a few of the early Fathers gladly assert with him in their preaching: "The knot of Eve's disobedience was untied by Mary's obedience: what the virgin Eve bound through her disbelief, Mary loosened by her faith" (Lumen Gentium, no. 56).What is the application for us? Assuredly we are called to give our lives completely to Christ in ways great and small (cf. Lk 19:11-27; 21:1-4). We must also accept with obedient faith Christ's teachings as preserved and proclaimed by the Church (cf. Lk 10:16). We should pray often for an increase of faith (cf. Lk 11:9; 17:5-6) and encourage each other (cf. Lk 22:32).

When it comes to living out our "obedient faith" in the concrete circumstances of our lives, we must carefully discern the Lord's voice and not turn back (cf. Lk 9:62; 18:28-30). We demonstrate our obedient faith by submitting to lawful authority out of love of God (cf. Lk 20:22-25). St. Paul even applies this principle to marriage: "Be subject to one another out of reverence for Christ" (Eph 5:21).

---------------------------------------------

Read the rest here

Friday, October 28, 2005

Consecration: Tenth Day

Imitation of Christ by Thomas a Kempis: Book 3, Chapter 10 (That it is sweet to despise the world and to serve God)

and

Prayers for Part 1

St. Louis de Montfort, pray for us!

St. Mary, pray for us!

Thursday, October 27, 2005

hell week

Sunday, the 30th, I'm helping serve a Mass for Cardinal McCarrick at the National Shrine in D.C. and then that night is a review session for my History of Philosophy mid-term on Tuesday.

Monday, the 31st, I have an Epistemology mid-term and need to start working on my Descartes and Nietzche paper for Philosophical Anthropology

Tuesday, the 1st, I have a History of Philosophy mid-term

Thursday, the 3rd, I have an Intro to Catholic Theology mid-term and my Aquinas paper for Philosophical Anthropology is due (more on that later).

Sunday, the 6th, the Vatican Visitation Team arrives at St. Mary's (not worried about that) and will be here till Friday, the 11th.

Monday, the 7th, I need to start prep for an Epistemology presentation and an Intro to Catholic Theology presentation. Plus my Political Philosophy paper is due (more on that later).

My Philosophical Anthropology paper is the following:

Read Summa Theologiae (1-2.18.1). Explain St. Thomas's argument and what significance it has for his overall understanding of the human person. Make sure you discuss the objections and replies. Keep the following questions in mind:

1. How does what St. Thomas says about human actions relate to his metaphysics - i.e. his understanding of the fundamental structures of reality?

2. How does what he says in 1-2.18.1 build upon the other texts you have read by Aquinas?

3. How does Aquinas' way of accounting for evil in human actions compare to Plato?

4-5 pages, typed, double-spaced.

My Political Philosophy paper is the following:

Give reasons from both a secular and a religious perspective why “gay marriage” has a negative impact on society. Use texts used in class, the Goodridge v. Dept. of Public Health decision, and Church Teaching from the Catechism, encyclicals, etc.

5 pages, typed, double-spaced.

Anyway, I'll be away from this blog for a while. When things calm down I'll post any pictures, thoughts, etc. and update on how the Consecration is going.

Our Lady of the Immaculate Conception, pray for us!

St. John Vianney, pray for us!

St. Charles Borromeo, pray for us!

St. Tarcisius, pray for us!

St. Thomas Aquinas, pray for us!

St. Augustine, pray for us!

St. Peter Lombard, pray for us!

St. Thomas More, pray for us!

St. Louis de Montfort, pray for us!

Consecration: Ninth Day

Imitation of Christ by Thomas a Kempis: Book 1, Chapter 13

and

Prayers for Part 1

St. Louis de Montfort, pray for us!

St. Mary, pray for us!

Wednesday, October 26, 2005

Consecration: Eighth Day

Imitation of Christ by Thomas a Kempis: Book 1, Chapter 13 (Of resisting temptations)

and

Prayers for Part 1

St. Louis de Montfort, pray for us!

St. Mary, pray for us!

Tuesday, October 25, 2005

Consecration: Seventh Day

Imitation of Christ by Thomas a Kempis: Book 1, Chapter 18

and

Prayers for Part 1

St. Louis de Montfort, pray for us!

St. Mary, pray for us!

Monday, October 24, 2005

Consecration: Sixth Day

Imitation of Christ by Thomas a Kempis: Book 1, Chapter 18 (On the examples of the Holy Fathers)

and

Prayers for Part 1

St. Louis de Montfort, pray for us!

St. Mary, pray for us!

Sunday, October 23, 2005

Consecration: Fifth Day

Imitation of Christ by Thomas a Kempis: Continued: Book 3, Chapter 40

and

Prayers for Part 1

St. Louis de Montfort, pray for us!

St. Mary, pray for us!

Saturday, October 22, 2005

Consecration: Fourth Day

Imitation of Christ by Thomas a Kempis: Book 3, Chapters 7 and 40 (That man has no good of himself, and that he cannot glory in anything)

and

Prayers for Part 1

St. Louis de Montfort, pray for us!

St. Mary, pray for us!

Friday, October 21, 2005

Consecration: Third Day

St. Matthew: Chapter 7:1-14

and

Prayers for Part 1

St. Louis de Montfort, pray for us!

St. Mary, pray for us!

Alumni Day

Here's some pics from the Mass, and my boy Mike giving quite the eloquent talk at the Alumni Day Dinner.

Do I spot a miter?...or three!

ah, yes... I need a moment here... OK, I'm good. A little P.O.D. at St. Mary's won't hurt anybody!

My d.b., Mike...I'm so proud!

Thursday, October 20, 2005

Consecration: Second Day

St. Matthew: Chapter 5:48, 6:1-15

and

Prayers for Part 1

St. Louis de Montfort, pray for us!

St. Mary, pray for us!

Wednesday, October 19, 2005

Consecration: First Day

St. Matthew: Chapter 5:1-19

and

Prayers for Part 1

St. Louis de Montfort, pray for us!

St. Mary, pray for us!

Consecration: Part 1

Theme: Spirit of the World

Examine your conscience, pray, practice renouncement of your own will; mortification, purity of heart. This purity is the indispensible condition for contemplating God in heaven, to see Him on earth and to know Him by the light of faith.

The first part of the preparation should be employed in casting off the spirit of the world which is contrary to that of Jesus Christ. The spirit of the world consists essentially in the denial of the supreme dominion of God; a denial which is manifested in practice by sin and disobedience; thus it is principally opposed to the spirit of Christ, which is also that of Mary.

It manifests itself by the concupiscence of the flesh, by the concupiscence of the eyes and by the pride of life, by disobedience to God's laws and the abuse of created things. Its works are: sin in all forms, then all else by which the devil leads to sin; works which bring error and darkness to the mind, and seduction and corruption to the will. Its pomps are the splendor and the charms employed by the devil to render sin alluring in persons, places and things.

Prayers to be Recited During These First Twelve Days:

Veni Creator

Come, O Creator Spirit blest!

And in our souls take up Thy rest;

Come with Thy grace and heavenly aid,

To fill the hearts which Thou hast made.

Great Paraclete! To Thee we cry,

O highest gift of God most high!

O font of life! O fire of love!

And sweet anointing from above.

Thou in Thy Sevenfold gifts art known,

The finger of God's hand we own;

The promise of the Father, Thou!

Who dost the tongue with power endow.

Kindle our senses from above,

And make our hearts o'erflow with love;

With patience firm and virtue high

The weakness of our flesh supply.

Far from us drive the foe we dread,

And grant us Thy true peace instead;

So shall we not, with Thee for guide,

Turn from the path of life aside.

Oh, may Thy grace on us bestow

The Father and the Son to know,

And Thee through endless times confessed

of both the eternal Spirit blest.

All glory while the ages run

Be to the Father and the Son

Who rose from death; the same to Thee,

O Holy Spirit, eternally. Amen.

Ave Maria Stella

Hail, bright star of ocean,

God's own Mother blest,

Ever sinless Virgin,

Gate of heavenly rest.

Taking the sweet Ave

Which from Gabriel came,

Peace confirm within us,

Changing Eva's name.

Break the captive's fetters,

Light on blindness pour,

All our ills expelling,

Every bliss implore.

Show thyself a Mother;

May the Word Divine,

Born for us thy Infant,

Hear our prayers through thine.

Virgin all excelling,

Mildest of the mild,

Freed from guilt, preserve us,

Pure and undefiled.

Keep our life all spotless,

Make our way secure,

Till we find in Jesus

Joy forevermore.

Through the highest heaven

To the Almighty Three,

Father, Son and Spirit,

One same Glory be. Amen.

Magnificat

My Soul doth magnify the Lord.

And my spirit hath rejoiced in God my Savior.

Because He hath regarded the humility of His handmaid; for behold, from henceforth all generations shall call me blessed.

Because He that is mighty hath done great things to me; and holy is His name.

And His mercy is from generation to generation, to them that fear Him.

He hath shadowed might in His arm; He hath scattered the proud in the conceit of their heart.

He hath put down the mighty from their seat; and hath exalted the humble.

He hath filled the hungry with good things, and the rich he hath sent empty away.

He hath received Israel His servant, being mindful of His mercy.

And he spoke to our fathers, to Abraham and to his seed forever. Amen.

Glory be to the Father, and to the Son, and to the Holy Spirit, as it was in the beginning, is now, and will be forever. Amen.

Total Consecration to Jesus Through Mary

Today is also the first day that Michael Wimsatt and I will be preparing for St. Louis Marie de Montfort's Total Consecration to Jesus Through Mary. Here's a brief intro to this devotion:

St. Louis de Montfort tells us that "those who desire to take up this special devotion" (Total Consecration to Jesus Through Mary), "should spend at least twelve days in emptying themselves of the spirit of the world, which is opposed to the spirit of Jesus. They should spend three weeks inbuing themselves with the spirit of Jesus through the most Blessed Virgin." (T.D. No. 227)

It is obvious that this total consecration, or perfect remewal of our baptismal vows with and through Mary, is not to be taken lightly. Pope John Paul II said that "Reading this book (St. Louis de Montfort's True Devotion to Mary) was to be a turning point in my life... This Marian devotion... has since remained a part of me. It is an itegral part of my interior life and of my spiritual theology." In his Marian Year encyclical, Mother of the Redeemer, speaking of Marian Spirituality, the Holy Father singles out: "among the many witnesses of his spirituality, the figure of Saint Louis Marie Grignion de Montfort, who proposes consecration to Christ through the hands of Mary, as an effective means for Christians to live faithfully their baptismal commitments." (No. 48)

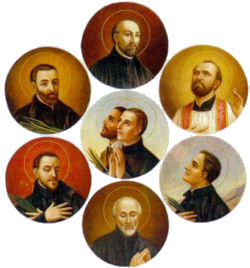

Michael and I chose this day to begin the 33 days of preparation because it's the Memorial of the North American Martyrs, which is kinda cool. And also because the Day of Consecration, the 34th day, Monday Nov 21, is the Memorial of the Presentation of the Blessed Virgin Mary. This is significant because the day of consecration must fall on a Marian memorial or feast day and also because it is the patronal feast day of St. Mary's Seminary. Our Chapel was founded on that day.

So, dear reader(s), please pray for me that I persevere during these 34 days, stay faithful to this devotion, and in so doing come closer to Christ through the guidance of his Blessed Mother.

I may try to post the prayers and readings that are required for each day and any thoughts I have along the way. But at the same time, I don't want this blog to be a distraction from the right-spirit I should have during this time so...we'll see.

St. Louis de Montfort, pray for us!

St. Mary, pray for us!

Holy See on I.T.

Holy See's Address on Information Technologies

"The Right to Communicate Is the Right of All"

NEW YORK, OCT. 18, 2005 (Zenit.org).- Here is the text of an address delivered by Archbishop Celestino Migliore, the Holy See's permanent observer to the United Nations, last Thursday before the U.N. General Assembly commission on "Questions Relating to information."

Mr. Chairman,

The Holy See recognizes the right to information and its importance in the life of all democratic societies and institutions. The exercise of the freedom of communication should not depend upon wealth, education or political power. The right to communicate is the right of all. Freedom of expression and the right to information increase and develop in societies when the fundamental ethics of communication are not compromised, such as the pre-eminence of truth and the good of the individual, the respect for human dignity, and the promotion of the common good.

Furthermore, new technologies have an important role to play in the advancement of the poor. As with health and education, access to the wealth represented by communications would certainly benefit the poor, as recipients of information to be sure, but also as actors, able to promote their own point of view before the world's decision makers.

Given the ever increasing ease of access to information of every possible kind, the Holy See also stresses the need to protect the most vulnerable, such as children and young people, especially in the light of the increase of content featuring violence, intolerance and pornography.

Perhaps the most essential question raised by technological progress is whether, as a result of it, people will grow in dignity, responsibility and openness to others.

In this context, the Holy See has set up a unique continentwide initiative called the Digital Network of the Church in Latin America ("Red Informática de Iglesia en America Latina" -- RIIAL) which promotes the adoption of digital technologies and programs in media education, especially in poor areas. The success of this project has drawn the attention of the Observatory for Cultural and Audiovisual Communication in the Mediterranean and in the World (OCCAM) and other international organizations. The Holy See also supports the continued promotion of the traditional role of libraries and radios in formation.

It is to be hoped that the Second Phase of the U.N. World Summit on the Information Society (WSIS), to be held in Tunis shortly, will lead to further concrete efforts to build a more inclusive digital society which will reduce the widespread "info-poverty." It would be well if a new dynamic were created which goes beyond the political and commercial logic usually at play in these fields.

My delegation believes that the Information Society should be one endowed with the ability, capacity and skills to generate and capture new knowledge and to access, absorb and use effectively information, data and knowledge with the support of information and communication technology. Already in society there are many "agents of meaning" or "knowledge workers," such as the family, schools, the state, opinion makers and leaders, not to mention religious institutions.

Knowledge is essential in establishing presence in the international marketplace, and is key to

participating in the global economy of which the Internet is an increasingly important vehicle. Moreover, knowledge should be recognized in its role in the development of information and communication technology. At the same time, there is a fundamental need to develop an ability to discern information received, given the enormous sea of information available. This process can flourish only where there is a recognized hierarchy of values.

Thank you, Mr. Chairman.

Monday, October 17, 2005

grades on papers

1. Philosophical Anthropology paper: A- (I tried to slip two or three ideas past the professor that I knew weren't properly developed... didn't fool him)

2. Intro to Catholic Theology paper: A

3. Epistemology paper: A

4. History of Philosophy paper: A

Prayer of Thanksgiving to Our Lady, Seat of Wisdom.

fourth paper

Here is my fourth paper, this one for History of Philosophy. This is an analysis of an article given to us by the professor. The article is “Rational Animal/Political Animal” by Laurence Berns, a tutor at St. John’s College, a famous “Great Books” college in Annapolis, MD.

Laurence Berns, in his piece, “Rational Animal/Political Animal,” focuses on the origin of philosophy; his main thesis being that philosophy “emerged among the Greeks as a result of the discovery of the idea of Nature.”[1] The first paragraph of the piece mentions that Aristotle “takes human speech very seriously” because it can lead to the “fundamental principles of all things.” From the very beginning, with the phrase “Aristotle takes human speech very seriously,” Berns is implying that, obviously, others do not. By looking carefully at speech and its fundamental function in articulating perceived contrasts in the way things work, one can understand the emergence of philosophy. Berns is implying that uncritical thinkers of human speech would miss this development or fail to appreciate it.

By starting the second paragraph with the “idea of nature” and placing it in the context of the “western tradition of thought,” Berns sets his discussion firmly on a nature-centered path to which we can relate. He then begins to detail how the fundamental issues of western thought were argued in terms of contrasts. Berns doesn’t necessarily list these contrasts in chronological order but, according to Dr. Paul Seaton, these can indeed be arranged into periods[2]: “Ancient” – Nature & Art and Nature & Convention; “Medieval” – Nature & Grace, Nature & Supernatural, and Nature & Divine; and, lastly, “Modern” – Nature & Freedom, Nature & Spirit, and Nature & History.”

By starting the third paragraph with “In fact Aristotle, among others, suggests” Berns implies that Aristotle was not alone in his understanding that “philosophy and science themselves come into the world with the discovery of nature.” By using the words “come into the world,” Berns implies the existence of a world that is pre-philosophy and even pre-science. Mentioning the “discovery” of nature further characterizes the world as not having a concept of nature either. More will be said of this later. Lastly, Berns then transitions to another thought by stating that “there were and still are people who have no distinct idea of nature” and that the word “nature” doesn’t appear in the Old Testament or in the Gospels but in Paul’s letters and other places in the New Testament. This transition shows that Berns is assuming we would expect to learn of nature from Scripture or that it is there where we would normally turn for answers.

Berns then goes into his account of life “before nature was discovered.” His point here is that life at this time was characterized by gods that ordained all things. “The gods ordered and commanded things to go in their customary ways.” This time, Berns mentions that his keyword “way,” contrary to his earlier keyword “nature,” occurs very often in Scripture. Here he implies that the Old Testament peoples and writers, and even those of the New Testament, were more familiar with a “ways-based” understanding of the world in which God was the main authority. According to this understanding, the gods (or God) specifically ordained natural events (i.e. fire, rain, crops, childbirth, etc.) and human events (i.e. what the people could eat or kill, punishment, retribution, etc.) to occur. Berns says, “The commands of the gods were delivered to the ancestors” and on down through the generations. This is how an understanding of the world was made known and populated. Furthermore, this reinforces, as stated in the beginning, the importance of speech.

Then Berns moves into his discussion of the discovery of nature and its impact on the worldview of those who began to understand it. He says that “some curious and thoughtful man” noticed some things are the same no matter what you do about them, and others vary whether you do something or not. By using the words “curious and thoughtful” he says that it took a certain special insight and mind to recognize these things. “We can glean, or hypothesize, at this point that philosophy is an intellectual operation based upon certain distinctions.”[3] Also here, Berns transitions from speaking about nature to speaking about necessity and in doing so equates them. Now instead of the contrasts being between Nature and Art, Convention, Grace, the Supernatural, the Divine, Freedom, Spirit, and History, they are between the Necessary and the Accidental; the Necessary and the Customary; and the Necessary and the Artificial. This new contrast is important because if things must happen out of necessity, then this leaves little room for the involvement of the gods.[4]

He goes on to hint that this change in understanding, or terminology, was due to the “curious and thoughtful” man “becoming” a traveler. He is now traveling when he didn’t before and this has expanded and refined his understanding of the way things work. This also leads him to a further discovery, that not only are some things the same independent of influence throughout a given place, but they are the same across several places and even, he concludes, universally: “some ways are the same everywhere.” But along with this comes the converse that some ways vary from place to place. Berns’ thoughtful-man has discovered that his way, the collective “Our Way” of which he is a part, is not exactly everyone’s “way.” Berns adds that “these contradictions are connected with even more fundamental contradictory opinions, concerning the very origin of the gods.” The origin of the gods is brought into question because, supposedly, they dictated all things to behave a certain way, but pre-philosophic man now realizes that this way isn’t always as universal as he thought.

With these discoveries, man begins to learn differently too. Instead of relying solely on “listening” to the elders as he did before (which is still legitimate), he can now learn truth by seeing for himself as well. Berns adds, “The suspicion begins to arise that what one can see to be everywhere the same is primary, permanent and fundamental and that the other things are secondary, transient and derivative.” He concludes that while the collective “Our Way” can vary from place to place, there is “The Way” of things, “the way according to nature, that which is right and good in itself because it is in accord with nature,” that is the same everywhere. Now man must decide if things are “right and good” because they are in accordance with nature or because they have been established by certain authorities, like the gods.

In the summary paragraph of this first line of thought, Berns uses the phrase “on the basis of the distinctions” to bring us back to his earlier stated goal. He has shown that philosophy emerged in western thought through an articulation of perceived distinctions between Nature/Necessity and other “forces.” Berns also adds a new distinction or rather a restatement of a fundamental distinction: the “old way” and the “right way.” This is a distinction between the “old way” of listening to commands of the gods passed down through the elders and the “new” and now characterized “right” way of appealing to both the elders and man’s own investigation. This moral judgment of the “new way” as “right” sets up his discussion for a brief and closing treatment, of the meaningful mission of both newly-emergent philosophers of the past and those of today. But before he does that he states another distinction important to his point: “way” is split up “into the notions of ‘nature,’ on the one hand, and ‘convention,’ on the other.” Dr. Seaton defines convention as “to agree to come together or something that owes its being to human agreement.”[5] Berns ends his summary paragraph by saying “philosophers and scientists begin to think that knowledge of this apparently impersonal necessity, nature, is the one thing most needful.” On why it is most needful, Berns doesn’t elaborate, other than what he implies with his “old” vs. “right” distinction.

At the beginning of a new line of thought on the meaningful mission of philosophers old and new, Berns states that “The distinction between what is good by nature and what is good by law, or by convention, good because it is posited, or legislated, becomes crucial for political and ethical philosophy.” This restates Berns’ pre-summary mention of the decision that his thoughtful-man must make as to the source of the “right and good.” Now, since the good, in general, is that which is “in accordance with nature, or good by nature,” conventions aren’t judged against or come from the gods but against/from nature. In the “new” and “right” way, sins aren’t an offense against the gods, but a “perversion” of nature.

In the last paragraph, in order to give a clear characterization of “philosophers,” he mentions that they can include “erring philosophers” and “imitators or images.” Such men called “sophists or intellectuals” abuse the distinction between nature and convention by blowing it out of proportion to discredit conventions as unreasonable and unnatural. They also seek to undermine conventions in order to undermine “ordinary decency.” This implies that conventions play a key role in ordinary decency.

The last three sentences of Berns’ essay clarify the mission of authentic philosophy. One permanent task should be to “defend ordinary pre-philosophic practical wisdom from sophistical attack and ordinary decency from sophistical scientism.” Because this follows his accusation that sophists undermine ordinary decency, he thereby equates ordinary decency with pre-philosophic practical wisdom. From the context of this second line of thought we can define “sophistical scientism” as an ideology that denied practical wisdom and convention by saying that all is nature and no other guide or force is needed. Sophists produce “corruption of the youth” but sophists and philosophers both pay for it because not only is the authentic philosopher doing his own work in the development of thought but he must also work to defend philosophy. By mentioning the “youth” Berns brings out the public and social impact that philosophy is capable of and so in his last sentence calls for “political” philosophy to “extricate philosophy from the opprobrium[6] brought upon it by its imitators.” The implied lesson of this essay then is that philosophers should be mindful of the same concerns expressed here anytime philosophy emerges anew or remerges in the ongoing development of western thought.

[1] Most of the quotes from this essay come from the Laurence Berns handout, “Rational Animal/Political Handout” from PHIL 301 History of Philosophy, St. Mary’s Seminary and University

[2] From notes given by Dr. Paul Seaton in the course, PHIL 301 History of Philosophy, St. Mary’s Seminary & University. Source and author hereafter referred to as “Dr. Seaton.”

[3] From notes from Dr. Seaton.

[4] Notes from Dr. Seaton say, “I indicated the deep importance of that claim by asking, where is the Creator, Providential, Redeemer God in a necessary/necessitated universe or nature?”

[5] From notes from Dr. Seaton.

[6] “opprobrium” is the “state of disgrace resulting from public abuse” (WordNet ® 2.0, © 2003 Princeton University)

Fr. Paul's homily for Sun Oct 2

October 2, 2005

Jesus was famous for using analogies... or parables as we also call them. He tried to make His message as understandable to the people of His time as He could. This often meant using examples that touched on the people’s lives in some way. Because His society was predominantly an agricultural one, in which the vast majority of people were engaged in growing fruits and vegetables, sheep or other animals for their subsistence, we have a lot of stories about farming. Today is no exception. Both Isaiah the prophet and Jesus use the same analogy in our scripture reading today. That of a vineyard. The ancient peoples were fond of their wine, so nearly every land owner would have had at least a few vines growing out back of their house. They would have understood easily the implications of this parable.

When we think of vineyards today we often have that image of row upon row of vines growing in the Napa valley, France, Italy, or other parts of the world known for their wine. A close inspection of these vineyards and the operations that go into growing grapes helps us to appreciate more fully this analogy that Christ and Isaiah use today. Growing grapes is an intense process. To produce the best grapes this process is dependent upon several factors: just the right mix of sun and rain, just the right temperature, and the perfect soil to nourish the root system. When all of these factors come together then the best grapes are created to produce the best wine.

Grape vines are very finicky things as well. They are made up of stringy branches that creep along low to the ground. They are inherently weak, and depend upon some structure to cling to for support. They take a great deal of tending and pruning to grow in the right direction and produce good fruit. After all this labor and effort, the vines, we can say, serve only one purpose: to produce the best possible fruit.

In our readings this weekend, a very clear parallel is made between this vine and you and I gathered here today. In the midst of a complex world, we are reminded today that our lives have one sole purpose: to produce fruit for the Lord. By this is our true purpose in this life fulfilled. A great deal of effort must go into the vine for us to produce this fruit. What’s more, we must have something solid to cling to so that we will be supported and have the opportunity to grow.

So what then is this fruit? Is it some physical thing that we are supposed to make? This is the tricky part. For the fruit that you and I are called to make in our lives is not a visible one, at least not physically. The fruit of our lives must be the love of God shown forth in the loving service of our neighbor. For this fruit to grow, we must cling to the teachings of the Lord, which provide us strength and support.

Just as the vine must be pruned and trained to grow upon the structure for support, we too must train ourselves to grow along the supporting structure of our faith. The scriptures this weekend remind us that there have been times, indeed the majority of human history, when we have strayed from this realization. Times when the vine has been tempted to live for itself, rather than to fulfill its true purpose. In these times, God has sent messengers to call the vine back to its original purpose. These messengers, the prophets, were each beaten and killed. Our scriptures this weekend tell us that God even sent His own Son into this vineyard, and the Son too was treated in the same way.

The message of the gospel this weekend primarily challenges us then to be open to the word of God. The truth is no one likes to be told when they are wrong. No one enjoys someone pointing out the errors of their ways. This is especially true when the error has to do with such fundamental areas of our life. While our temptation may be to conform the challenging words of the scriptures and the Church’s teachings to accommodate our own desires, our challenge is to always conform ourselves to the word of God. It is only when we are able to do this that we are able to grow to our full potential and our lives produce the best fruit.

Fr. Paul Beach

Friday, October 14, 2005

Pre-Theology Ministry Log 01

Here's the first one:

Pre-Theologian Ministry Log

Date: Oct 13, 2005

Event: St. Ambrose Family Outreach Center: Helped a young black girl in the 9th grade with a computer project, tutored an older black lady in math who was studying for her G.E.D.

Name the feelings you experienced during the event: The girl was working on a project in which she had to research one of the top black colleges and universities in the country that was assigned to her and then create a calendar on the computer putting a different fact about the school on each day. I helped her find two different sources of information online for Howard University. I was surprised at how well she was able to gather the information she already had before I started helping her. I was also surprised at how open she was to my help and how comfortable she seemed around me. I had expected some hesitancy on the part of the teens to work with someone new to the center. After I helped her, I overheard two ladies at the front desk wondering why the spacing was off on an outline they were preparing for a class the next day. I suggested the “tabs” were off and was able to fix it for them. They were very thankful. I was then asked if I could tutor an older black lady in Math. One of the ladies at the front desk said that she had given her some trouble and “she’ll talk your ear off.” I thought that was a little unprofessional but then I realized that the atmosphere was very laid back and all of the folks there at the center seemed to have a great relationship with the volunteers. When I started to help her I found her to be very pleasant and I enjoyed working with her. She seemed to enjoy it too and was also very thankful. I think I helped her learn the set of problems she was working on too. Overall it was a very positive experience. Honestly, being the only white person there, I expected some walls to be up initially. But it wasn’t like that at all. I felt good about myself, working with the younger girl, the ladies at the front desk, and the older lady. A young lady in charge of the teens was very excited to know I worked as a software developer for three years prior to seminary. I think she was a little unsure how this calendar project was going to pan out. I felt very good helping the people there.

What was difficult and or troubling? Why? Nothing difficult or troubling except for the slight remorse I felt for underestimating the people there.

Where was God in this event? There was a Sister in charge there, working with the folks studying for their G.E.D. So of course, God was there in her. And when Vic and I would introduce ourselves as being from St. Mary’s people seemed genuinely happy to hear that. That was comforting.

What have you learned about yourself in the wake of this event? That I like helping people learn. I want to be a positive influence very much, especially with the teens.

Wednesday, October 12, 2005

my individual shot

I think it looks a little too Photoshop'd, like I got makeup on or somethin'!

vocation office group photo

On the bottom is Pablo Hernandez, to be ordained deacon on Dec 20, 2005. On the step up from him is Archbishop Thomas Kelly and Deacon Wally Dant. Next up from them is Linda Banker, Associate Vocation Director and Kit Afable. Kit just completed minor seminary and is taking a year off because at the rate he's going, he'll be canonically too young to be ordained a priest in four years (you have to be at least 25). At the top are Fr. Bill Bowling, the Vocation Director, myself, and my fellow seminarian at St. Mary's, Michael Wimsatt. I am in Pre-Theology and Michael is in 2nd Theology. My prediction: In ten years from now the number of seminarians in this picture, five, will have tripled :)

Monday, October 10, 2005

third paper

In Plato’s Euthyphro[1], we have the famous dialogue on the definition of piety, featuring Plato’s preeminent teacher, Socrates. He and his acquaintance Euthyphro meet outside a court building of Athens, each there for very different reasons. Socrates is being prosecuted for, namely, impiety:[2] “corrupting the youth (cf. 2c)” and being a “maker of gods”[3] while not believing in the “old gods” of Athens (cf. 3b). Euthyphro is there to prosecute his father for the murder of his servant who had committed murder as well. This dialogue, on the surface, can seem to be merely an inconsequential discussion between two citizens on their way to court. Or it can seem to be merely a selfish task on Socrates’ part to hammer out a definition of piety from his all-knowing acquaintance[4] so he can use it to his defense in his forthcoming trial. But a closer look reveals a dialogue that, through key phrases and attitudes, yields keen insight into the Socratic understanding of the range and content of human knowledge, the process by which one acquires knowledge, and the role the gods are accorded in the process.

Outside of the court building, after Euthyphro explains his reason for being there, “Socrates is surprised, and Euthyphro seems (is reputed to be) mad [cf. 4a], because murder prosecutions were ordinarily brought by a member of the family of the victim, certainly not by someone from the family of the alleged murderer.”[5] Socrates asks him, “Whereas, by Zeus, Euthyphro, you think that your knowledge of the divine, and of piety and impiety,[6] is so accurate that, when those things happened as you say, you have no fear of having acted impiously in bringing your father to trial?” And Euthyphro replies, “I should be of no use, Socrates, and I would not be superior to the majority of men, if I did not have accurate knowledge of all such things.” So we see early in the dialogue a hint towards the idea that knowledge of the divine is what is most important.

With the divine comes the overall theme of the dialogue, “What is piety?” (cf. 5d) And in Socrates’ search for a definition of piety we have an illustration of the “Socratic search for universal definitions of ethical terms” that recurs in many Platonic dialogues:[7]

What kind of thing do you say that godliness and ungodliness are, both as regards murder and other things; or is the pious not the same and alike in every action, and the impious the opposite of all that is pious and like itself, and everything that is to be impious presents us with one form[8] or appearance insofar as it is impious? (ibid.)

Euthyphro gives an example of piety, his own act of prosecuting his father, rather than a definition of piety[9] that Socrates was looking for. So Socrates replies, “you did not teach me sufficiently earlier, comrade, when I asked what ever the pious is. Instead, you told me that what you are now doing… happens to be pious.” And:

I didn’t bid you to teach me some one or two of the many pious things, but that eidos itself by which all the pious things are pious… For surely you were saying that it is by one idea that the impious things are impious and the pious things are pious.[10]

So the following can be concluded, concerning the Socratic understanding of the content of human knowledge: it is that which concerns the divine and can be universally defined. This essay is concerned with this type of human knowledge as it is Socrates’ focus throughout the dialogue and provides a look into his attitude toward human knowledge in general. Socrates’ understanding of the range of this content gives us an even broader look, a look into human nature as a whole: How much can we know, especially of the divine, and how well can we really know it? Euthyphro gives us some clues.

First it is indicated several times throughout the dialogue that this knowledge of the divine, and things pertaining to it, piety, justice, etc, are not easily grasped. When asked in the beginning what charge is being brought against him, Socrates replies, “it is no small thing for a young man[11] to have knowledge of such an important subject;” that is, the good of the young against the supposed corruption of Socrates’ “made up gods” and ignorance of the “old ones.” When Socrates in turn discovers that Euthyphro’s business at the court is to prosecute his father for murder, an act with a high risk of impiety (cf. 4e, 15d-e), he cautions him by saying, “most men would not know how they could do this and be right. It is not the part of anyone to do this, but of one who is far advanced in wisdom (4b).” Lastly, later in the dialogue, one of the many definitions Euthyphro posits for piety is “that the godly and pious is the part of the just that is concerned with the care of the gods, while that concerned with the care of men is the remaining part of justice (12e).” Soon, Socrates refines “care of the gods” to mean “a kind of service to the gods (13d).” When he then asks Euthyphro what the purpose of such service would be, Euthyphro replies, “it is a considerable task to acquire any precise knowledge of these things.” This is in fact so difficult a task that Socrates exclaims toward the end of the dialogue, “I shall not willingly give up before I learn this (15d).” But, alas, in the end Euthyphro finally brushes him off as it is time for him to go. So, clearly, the range of human knowledge, especially of the divine, though noble and worthily sought, may be considered quite narrow, indeed making it difficult to grasp. Taken as a commentary on human knowledge in general, this betrays a bleak outlook on both the ability of man to grasp higher knowledge and of how much of that knowledge is available to him in the first place. Nonetheless, Socrates has clear processes, illustrated in Euthyphro, for trying to acquire this knowledge anyway.

The most obvious process is the use of his famous method for discovering the truth of any given topic: dialectics. With this method Socrates questions those that he or the public considers wise. When engaged in a dialogue with one of these, he questions him as to the reasoning and coherence of every nuance of his argument in order to root out any contradictions or inconsistencies. Only after an argument has withstood this arduous test is it considered true and worth knowing. Subjected to this test, Euthyphro goes from being an “all-knowing acquaintance (n. 4)” to “being Daedalus,” or even worse (15b).[12]

Other clues into Socrates’ understanding of the processes by which one acquires knowledge are found in various comments he makes throughout the dialogue. For example, in section 9e, when Euthyphro defines piety, this time, as being “what all the gods love, and the opposite, what all the gods hate, is the impious,” Socrates replies, “Then let us examine whether that is a sound statement, or do we let it pass, and if one of us, or someone else, merely says something is so, do we accept that it is so? Or should we examine what the speaker means?” Here, Socrates addresses the method that he thinks most men of Athens use: mere assertion. The ramifications of this method strike deep. When Euthyphro at the beginning of his dialogue with Socrates claims that the Athenian public, or more specifically, the “assembly,”[13] is envious of their wisdom, Socrates replies, “the Athenians do not mind anyone they think clever, as long as he does not teach his own wisdom, but if they think that he makes others to be like himself they get angry, whether through envy, as you say, or for some other reason (3c-d).” Here he implies that no one comes to knowledge of truth by his own investigation but rather by merely going along with the “publicly declared principle of the herd.”[14] And this is largely conceived by what is most “nobly”[15] asserted in court cases. Speaking of Meletus, Euthyphro says, “So he has written this indictment against you as one who makes innovations in religious matters, and he comes to court to slander you, knowing that such things are easily misrepresented to the crowd (3b).” The assembly is a “dull-witted jury (9b)” that never takes seriously arguments that go against popular opinion and those with influence aren’t willing to make such arguments anyway. “If they are going to be serious, the outcome is not clear except to you prophets (3e).”

Another method the public (including Euthyphro and Socrates) uses is to look to the divine itself, the gods. And this leads us to Socrates’ understanding of the role the gods are accorded in the process of acquiring knowledge. Starting with Socrates himself, Euthyphro tells us that the reason Socrates is being prosecuted as a “maker of gods” is because his “divine sign” keeps coming to him (cf. 3b).[16] This divine sign, or voice, intervenes regularly only to “prevent him from doing or saying something, but never positively.” Euthyphro says that he too can “speak of divine matters in the assembly” and hints that this divine sign that they supposedly share enables them to “foretell the future.” (cf. 3c) But, “Socrates dissociates himself from ‘you prophets (3e).’”[17]

Socrates is more critical of the way the public uses the divine for their knowledge of the truth by trusting the stories of the gods. These stories, told by the great poet Homer, are passed down from generation to generation through popular opinion and belief. This is most evident in the charges against Socrates that he makes new gods while ignoring the ones that the city worships. This greatly angers the common sensibilities of the assembly and the larger public. Also, Euthyphro is a microcosm of this:

Euthyphro takes his bearings from the stories told by poets and others about Zeus and the gods... So when Euthyphro is asked what the pious is, his first answer is prosecuting wrongdoers, and his proof is the story that Zeus bound his father Kronos. Just as Zeus attacked Kronos, so Euthyphro is prosecuting his own father for murder. In other words, we may infer, piety as Euthyphro understands it is imitating the gods.[18]

Socrates feels that Euthyphro and the larger public place too much trust in the stories of the gods. He questions the role of the gods as a source of knowledge. First, Socrates wonders how they can be trusted at all because according to the stories, “the gods are in a state of discord, they are at odds with each other, and they are at enmity with each other (7b)” and “different gods consider different things to be just, beautiful, ugly, good, and bad (7e).” Also, “the same things then are loved by the gods and hated by the gods (8a).” Socrates asks if they never agree, if nothing is universally true among them, how can it be true for the people? He concludes, “I prefer nothing unless it is true (14e).” And he also says, “I find it hard to accept things like that being said about the gods [that they disagree], and it is likely to be the reason why I shall be told I do wrong (6a).” If Euthyphro can give him a sign that all the gods believe his action against his father to be right then Socrates “shall never cease to extol [his] wisdom (9b).”

Lastly, we can infer that the criticism Socrates has for mere public assertions he has for mere divine assertions as well. Is something good (or true) because some authority (the gods) says it is or because of some characteristic inherent in it? This is the difference between “Moral Voluntarism” and “Moral Realism,”[19] respectively, and Socrates makes a good argument for Moral Realism. “Is the pious loved by the gods because it is pious, or is it pious because it is loved (10a)?”[20] Socrates’ engagement of Euthyphro in dialectics concerning this question is what puts Euthyphro’s arguments in circles (cf. n. 15). One commentary of this idea concludes:

If the gods are guided by knowledge and do not give merely willful commandments [or “assertions”], the guidance provided to men by divine law must be superfluous for one who is wise enough to discover for himself the truth of the good, noble, and just. The wise man has no need of gods. (4T, p. 14 of “Plato’s Euthyphro.”)

In addition, “the principle by which Socrates’ piety – if that is what it is – is governed is not ‘Zeus’ or traditional customs, but reason (p. 15).”

Yet, although he doubts the traditional stories, Socrates asserts that all good things come from the gods (15a)… and that the pious is part of the just (12d). He may mean that the terms of man’s obligations to gods flow from a consideration of the altogether human virtue if justice, which… is concerned with the right order of the political community and of the human soul (p. 15)[21]

Therefore, Socrates’ understanding of the role that the gods are accorded in the process of acquiring knowledge is one of value but also one that is tempered by sound reasoning and concern for the common good. Divine knowledge must not become “holy passion”[22] (as is the case of Euthyphro prosecuting his father) and must also not be taken for granted (as in the public’s unquestioned, popular acceptance of unreasonable stories as truth).

At the end of the dialogue, Socrates points out that Euthyphro’s arguments have gone in circles and that they are back where they started. Socrates pleads for him to persevere, “Do not think me unworthy, but concentrate your attention and tell the truth. For you know it, if any man does, and I must not let you go, like Proteus,[23] before you tell me (15d).” Socrates has high hopes that he can “learn from [Euthyphro] the nature of the pious and the impious and so escape Meletus’ indictment.” But, Euthyphro leaves him unsatisfied and with nothing to show Meletus that he is “no longer acting unadvisedly because of ignorance (16a).”[24] Despite his humility though, one can see in Socrates’ understanding of the content, range, method and source of human knowledge that he is the wiser of the two. It will be through Meletus’ ignorance and by “attempting to wrong” Socrates that the “very heart of the city” will be harmed (cf. 3a).

[1] In this essay, I use the translation of Euthyphro from Plato: Five Dialogues, 2nd ed., translated by G.M.A. Grube, revised by John M. Cooper, ©2002, Hackett Publishing Company, Inc, hereafter referred to as “P5.” I also refer to a different translation of Euthyphro in Four Texts on Socrates, Plato, and Aristophanes, revised edition, translated with notes by Thomas G. West and Grace Starry West, ©1998, Cornell University press, hereafter referred to as “4T.” All quotes from Euthyphro are of the former translation unless indicated otherwise.

[2] Impiety was considered a “serious offense.” P5, p. 2, n. 2 says, “The king-archon, one of the nine principle magistrates of Athens, had the responsibility to oversee religious rituals and purifications, and as such had oversight of legal cases involving alleged offenses against the Olympian gods, whose worship was a civic function – it was regarded as a serious offense to offend them.

[3] Socrates states that he is charged for being a “maker of gods” when Euthyphro asks him, “Tell me, what does [your prosecutor] say you do to corrupt the young?” 4T, p. 42, n. 9 says that “The word translated ‘do’ is poiein, the same word translated “make” in Socrates’ reply. The word “maker” is poietes: Socrates is accused of being a ‘poet’ of gods.” And since the great poet Homer is the foundation for all Greek morality, the one who established all the great stories of the gods, this is quite a serious charge.

[4] P5, p. 2, n. 1 says he is a “professional priest.” Also cf. 5a, 9b, 12a, 13e, 14d, etc.

[5] 4T, p. 44, n. 13.

[6] In any bold statements throughout, emphasis mine.

[7] Cf. P5, p. 1, introduction to Euthyphro

[8] P5 uses “form” but 4T uses “idea,” leaving the Greek word used here untranslated. 4T, p. 46, n. 20 says, “the word eidos, of similar meaning, is also left untranslated at 6d below. These are the terms used by Plato in his so-called doctrine of ideas (e.g. “the idea of the good,” Republic 505a). The idea or eidos of a thing may be thought of as the look it has, in the mind’s eye, when it is truly seen for what it is.”

[9] Also cf. 9b, 11b, and the end of 15e which says, “nature of the pious and the impious.”

[10] This quote and the one before it are both from the 4T translation, 6d-e.

[11] The “young man” is Socrates’s prosecutor, Meletus. (n. 3)

[12] Cf. 11c. Socrates compares Euthyphro’s statements to the person of “Daedalus, a legendary Athenian master craftsman and inventor who was reputed to have constructed statues that could move about by themselves (4T, p. 54, n. 33).” In 15b Socrates goes on to say that not only do Euthyphro’s arguments “move about” from one conclusion to another, they also go in circles!

[13] P5, p. 3, n. 5 says, “The assembly was the final decision-making body of the Athenian democracy. All adult males could attend and vote.”

[14] 4T, p. 15 of “Plato’s Euthyphro”

[15] In P5, 9e, quoted above, Socrates asks Euthyphro if his is a “sound statement” wile 4T uses the phrase “said nobly.” For the Greeks “something is ‘nobly’ (or ‘beautifully’) said when it is spoken aptly and to the point (though perhaps not in every case truly: see 7a). The word is kalon (4T, p. 52, n. 28).” Apparently Socrates isn’t very “apt and to the point,” at least not in the popular sense of “noble” speech.

[16] P5 uses “divine sign” but 4T uses “daimonion.” Socrates explains “his daimonion, his daimonic or divine sign, in Apology 31c-d. The actual impiety charge against him was: ‘He does not believe in the gods in whom the city believes, and he brings in other daimonia [divine or daimonic things] that are new.’ See Apology nn. 37, 38, 56 (4T, p. 43, n. 10).”

[17] The last three sentences of this paragraph: cf. P5, p. 3, n. 4

[18] 4T, p. 13 of “Plato’s Euthyphro”

[19] From notes on Euthyphro given by Dr. Frederick C. Bauerschmidt in Phil 230: Philosophical Anthropology

[20] 4T translation used here

[21] Cf. Euthyphro’s statement after the prompting of Socrates, 14b

[22] 4T, p. 15 of “Plato’s Euthyphro”

[23] Proteus, an immortal and unerring old man of the sea who serves the god Poseidon, answers the questions of mortals if he can be caught and held fast, although he attempts to escape by assuming the shapes of animals, water, and fire. Menelaus, instructed by the goddess Eidotheia (“divine eidos” [cf. n. 8]), with difficulty succeeds in catching Proteus and learns what he must do to return home safely after the Trojan War from Egypt, where he has been stranded by contrary winds: he must offer sacrifices to Zeus and the other gods. (Odyssey IV. 351-569)

[24] 4T translation used here. The sentence before this is from P5. Both are from 16a.

second paper

Around 20 or 30 years after the passion, death, resurrection, and ascension of our Blessed Lord, St. Paul the Apostle wrote a letter to the Roman Church at Philippi, his first and faithful flock.[1] In it he thanks them for sending Epaphroditus to aid him while he was imprisoned and also exhorts them to persevere in the faith.[2] One particular passage of this letter, Phil 2: 5-11, is short but dense with insight. In this essay the revelation of this passage will be combined with the teachings of the Second Vatican Council in Sacrosanctum Concilium and the Catechism of the Catholic Church[3], particularly numbers 456-570. The resulting combination should provide a very important lesson for contemporary American Catholics on the reality of Jesus Christ, his sacrifice on the Cross, and what that means for our pilgrim fellowship of faith.[4]

In understanding Philippians 2:5-11, it is helpful to break down the passage into parts and look at the meaning of each part. This passage begins with the phrase, “Have this mind among yourselves, which was in Christ Jesus (v. 5).” We will see from the following verses that St. Paul is calling the Philippians and us to think, act, and identify with Christ’s humble and obedient death on the cross. St. Paul is not saying we should literally mimic his torture, but rather the virtues displayed in it, with our entire being. We should humble ourselves and die to our pride for the benefit and well-being of others. It is through this Way of the Cross that we too can hope for future glory with the Father.

Continuing further, verses six through eight say, “who, though he was in the form of God, did not count equality with God a thing to be grasped, but emptied himself, taking the form of a servant, being born in the likeness of men. And being found in human form he humbled himself and became obedient to death, even death on a cross.” Here St. Paul gives us a statement of Christ’s divinity when he says Christ was in the “form of God,” for a form is the “external aspect of something and manifests what it is.”[5] This statement seems clear enough, but then what does the Apostle mean when he says Christ “did not count equality with God a thing to be grasped”? The Greek used here, behind the words “equality” and “grasped,” gives us a clue. By equality (isos) he means “equality of rights and status” and by grasped (harpagmos) he means “to be seized upon or to be held fast.”[6] So our Lord, in his divinity, could have demanded to be treated with the dignity and respect that his divinity deserves. But he did not wish to “hold fast” to these rights of his. Instead he “emptied himself”, setting aside his rights and status so he could be in the “form of a servant,” the form of a man, like us in all things but sin (cf. Heb 4:15). He did this so he could suffer with men, as men, for men and thus redeem man’s “likeness” that was distorted after the fall. Finally, in stating that he “humbled himself,” St. Paul teaches that Christ acted of his own free will to obey the Father and submit to his passion. “Debasing oneself when one is forced to do so is not humility; humility is present when one debases oneself without being obliged to do so.”[7]

Finally, verses nine through eleven reveal the goal, purpose, and hope of Christ’s passion: “Therefore God highly exalted him and bestowed on him the name which is above every name, that at the name of Jesus every knee should bow, in heaven and on earth and under the earth, and every tongue confess that Jesus Christ is Lord, to the glory of God the Father.” Now the degree in which Christ humbled himself is the degree in which he is exalted: “highly” and with the glory he deserves. This is the same magnificent glory that blinded the eyes of the Apostles Peter, James, and John at the Transfiguration (cf. Mt 17:1-6; Jn 1:14). Where he was once the “criminal” (cf. Lk 23:2, 5, 32) on the cross, now he has been given the “name which is above every name”[8] and dominion over the entire universe (cf. Dan 7:14). This exaltation demands our praise and our worship (cf. Is 45:23-25). Here also, Christ gives us the perfect example of meaning and purpose in suffering. “If we obey God’s will, the cross will mean our own resurrection and exaltation. Christ’s life will be fulfilled step by step in our own lives.”[9]

Therefore the primary truth of Christ that is revealed in this passage is this: That out of love for mankind the Word took on our human nature to live among us; drew us to himself; taught us the way to salvation; and manifested his love by dying on the cross and restoring us to the Father. But, there is more to be said of this truth that is beneficial for our own Way of the Cross; the Vatican II document, Socrosanctum Concilium[10], contains further insight. SC serves to both briefly expound on the meaning behind the Mass and to decree certain norms and reforms of the Sacred Liturgy and the other elements in the life of the Church. This is not irrelevant in a discussion of the reality of Christ, “For the liturgy,” SC states early on, ‘through which the work of our redemption is accomplished,’ most of all in the divine sacrifice of the eucharist, is the outstanding means whereby the faithful may express in their lives, and manifest to others, the mystery of Christ and the real nature of the true Church (SC 2).”[11]

SC provides further relevance to the Philippians passage by relating the meaning of Christ’s passion, death, resurrection, and ascension not only to the Sacred Liturgy as a whole but to the Mystery of the Eucharist itself in particular. With these SC shows us that the whole liturgical life of the Church and all the elements of her worship (like sacramentals, the Divine Office, the Liturgical Year, and even Sacred Music) are bound up in Christ’s sacrifice on the cross and directed toward our salvation. In the Liturgy, the prayers and responses lift up and point our hearts to the Hill of Calvary, where our Lord says, “Come up hither (Rev 4:1).” In the Memorial Acclamation the faithful say, “Dying, he destroyed our death and, rising, he restored our life (SC 5).”[12] SC, concerning one of the prayers of the priest, also points out that:

We must always bear about in our body the dying of Jesus, so that the life also of Jesus may be made manifest in our bodily frame (cf. 2 Cor. 4:10-11). This is why we ask the Lord in the sacrifice of the Mass that, “receiving the offering of the spiritual victim,” he may fashion us for himself “as an eternal gift” (Secret for Monday of Pentecost Week). (SC 12)

Furthermore, in the Eucharist, the Church constantly celebrates the paschal mystery:

At the Last Supper, on the night when He was betrayed, our Savior instituted the Eucharistic sacrifice of His Body and Blood. He did this in order to perpetuate the sacrifice of the Cross throughout the centuries until He should come again, and so to entrust to His beloved spouse, the Church, a memorial of His death and resurrection: a sacrament of love, a sign of unity, a bond of charity[13], a paschal banquet in which Christ is eaten, the mind is filled with grace, and a pledge of future glory is given to us.[14] (SC 47)

But there is another important part of the Mass that should be mentioned: the Creed, and in particular that part of the Creed which proclaims, “He was conceived by the power of the Holy Spirit and was born of the Virgin Mary.” The Catechism’s treatment of this part in numbers 456-570 completes our task of a fuller understanding of Phil 2:5-11.

Here the Catechism is helpful in explaining further what the Philippians passage means by saying that Jesus was in the “form of God” and in “human form.” The Church has done well, in response to numerous heresies in her history, to refine her understanding of Christ’s dual nature. This can be confusing but the Catechism clearly states: Christ is not part God and part man but wholly each, “inseparably true God and true man (cf. CCC 464, 469).” He is “consubstantial with the Father as to his divinity and consubstantial with us as to his humanity.” He has two natures “without confusion, change, division, or separation and the distinction between these natures was never abolished by their union (cf. 467).”[15] Christ also assumed not only a human nature but a human soul with human knowledge that was finite. This is how he was able to “increase in wisdom and in stature” (Lk 2:52) and learn the skills of a carpenter from his foster-father, St. Joseph. The things of a lower order, skills, techniques, and what we only learn through experience, our Blessed Lord had to learn as well. But things of a higher order, his Father’s will, the state of our souls and hearts, and the thoughts on our minds, our Blessed Lord knew by being in union with the eternal Word (cf. 473-474).[16]

Of the other many truths revealed in this section of the Catechism, one in particular gives special insight into the reality of Christ, namely, that the mystery of redemption was at work in Christ’s entire life, culminating with what is revealed in Philippians and enlivening the teachings in SC. Through his Incarnation he enriches us with his poverty. Through his submission to the direction of his parents in his hidden life, silent in the gospel, he atones for our disobedience. In his public ministry, “his word purifies its hearers” and his healings and exorcisms “took our infirmities and bore our diseases.” Finally in his Resurrection he justifies us (cf. CCC 517).[17] Throughout, he humbled himself to be our example, his prayer draws us to pray, and his poverty calls us to accept freely our persecutions (cf. CCC 520).[18]