Art Is Servant

God Bless you Dave!

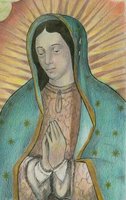

The Solemnity of the Immaculate Conception of the Blessed Virgin Mary

Plenary Indulgence Attainable on Dec. 8

Papal Decision for 40th Anniversary of Close of Vatican II

VATICAN CITY, NOV. 30, 2005 (Zenit.org).- Benedict XVI is offering the faithful a plenary indulgence on the solemnity of the Immaculate Conception, Dec. 8, the 40th anniversary of the close of the Second Vatican Council.

The indulgence was announced in a decree published in Latin on Tuesday, signed by Cardinal James Stafford and Conventual Franciscan Father John Girotti, penitentiary major and regent, respectively, of the Apostolic Penitentiary.

The document establishes that when the Pope renders public homage to Mary Immaculate in Rome's Piazza di Spagna, he "has the heartfelt desire that the entire Church should join him, so that all the faithful, united in the name of the common Mother, become ever stronger in the faith, adhere with greater devotion to Christ, and love their brothers with more fervent charity."

"From here -- as Vatican Council II very wisely taught -- arise works of mercy toward the needy, observance of justice, and the defense of and search for peace," adds the decree.

For this reason, the decree continues, the Holy Father "has kindly granted the gift of plenary indulgence which may be obtained under the usual conditions (sacramental confession, Eucharistic Communion and prayer in keeping with the intentions of the Supreme Pontiff), with the soul completely removed from attachment to any form of sin, on the forthcoming solemnity of the Immaculate Conception, by the faithful if they participate in a sacred function in honor of the Virgin, or at least offer open testimony of Marian devotion before an image of Mary Immaculate exposed for public veneration, adding the recitation of the Our Father and of the Creed, and some invocation to the Virgin."

At home

The document concludes by recalling that faithful who "through illness or other just cause" are unable to participate in a public ceremony or to venerate an image of the Virgin, "may obtain a plenary indulgence in their own homes, or wherever they may be, if, with the soul completely removed from any form of sin, and with the intention of observing the aforesaid conditions as soon as possible, they unite themselves in spirit and in desire to the Supreme Pontiff's intentions in prayer to Mary Immaculate, and recite the Our Father and the Creed."

On Dec. 8, 1965, Pope Paul VI, in closing Vatican II, dedicated great praise to the Blessed Virgin who, as Mother of Christ, is Mother of God and spiritual Mother of all mankind.

Benedict XVI Encourages Teaching of Latin

Greets Members of Latinitas Foundation

VATICAN CITY, NOV. 28, 2005 (Zenit.org).- Benedict XVI encouraged the teaching of Latin, especially to young people, with the help of new methodologies.

The Pope made this proposal today when greeting the participants in a meeting organized by the Latinitas Foundation, a Vatican institution that promotes the official language of the Latin-rite Catholic Church.

The Holy Father, who addressed the participants in classical Latin, congratulated the winners of the Certamen Vaticanum, an international competition of Latin prose and poetry.

Benedict XVI said that this foundation must see to it that Latin continues to be part of the daily life of the Church, so that understanding of many of its treasures will not be lost.

The Latinitas Foundation, founded by Pope Paul VI in 1976, has the dual aim of promoting, on the one hand, the study of Latin and classical and Christian literature, and on the other, the use and spread of Latin through the publication of books in that language.

The foundation publishes a quarterly magazine, Latinitas, and every year celebrates the Certamen Vaticanum. The foundation has also published a dictionary, the Lexicon Recentis Latinitatis, containing more than 15,000 neologisms translated into Latin.

For those who ever wondered about the Latin equivalent for "computer," "terrorist" or "cowboy," there are now answers.

"Instrumentum computatorium" is the way the Latinitas Foundation refers to computers.

Those who sow violence and terror are called "tromocrates (-ae)"; while characters in Westerns are called "armentarius."

Some of the words of the Lexicon Recentis Latinitatis can be consulted on the foundation's Web page.

See here.

Eucharist and Marian Devotion

Perspective of Theologian Father Michael Hull

NEW YORK, NOV. 20, 2005 (ZENIT.org).- Here is the text of a talk given by Father Michael F. Hull, who participated in the recent videoconference of theologians on the topic of the Eucharist. The Vatican Congregation for Clergy organized the event. Father Hull is a professor of sacred Scripture at St. Joseph's Seminary in Yonkers, New York.

* * *

The Holy Eucharist and Marian Devotion

Michael F. Hull

Devotion to the Holy Eucharist and devotion to Our Lady are so closely bound as to be inseparable. As Mother and Son are united in an "indissoluble tie" ("Lumen Gentium," No. 53), so too devotion to Mother and Son are tightly linked. This is expressed most beautifully by the medieval religious poem "Ave Verum," immortalized as a motet by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart in 1791.

In his encyclical letter "Ecclesia de Eucharistia," the late Pope John Paul II devotes the sixth and final chapter to Mary, which he entitles "At the School of Mary: 'Woman of the Eucharist.'" Therein, the Pope points out significant parallels in the lives of Jesus and Mary.

For example, Jesus' words at the Last Supper -- "Do this in remembrance of me" (Luke 22:19) -- echo Mary's words at the wedding at Cana -- "Do whatever he tells you" (John 2:5). Likewise, Mary's fiat to the Archangel Gabriel (Luke 1:38) prefigures the Amen of each communicant at the reception of Holy Communion.

Speaking of Mary's own reception of holy Communion after the Lord's paschal mystery, John Paul remarks: "For Mary, receiving the Eucharist must have somehow meant welcoming once more into her womb that heart which had beat in unison with hers and reliving what she had experienced at the foot of the Cross" ("Ecclesia de Eucharistia," No. 56). "Mutatis mutandis," we are also brought to the foot of the Cross in holy Communion, where we are united not only with the Lord, but also with the "stabat Mater dolorosa."

Finally, we find Our Lord entrusting his Mother to St. John, who as the "beloved disciple" had such a prominent place at the bosom of Jesus at the Last Supper, and St. John to his Mother (John 19:26-27). Holy tradition recounts how Mary and St. John eventually settled at Ephesus, the place where Mary kept so much in her heart until her assumption (cf. Luke 2:33-35 and 2:51).

During the public ministry of the Lord, Mary is rarely in the foreground. Except for the wedding at Cana -- when Jesus prefigured his miracle of the Eucharist by turning water into wine at Mary's request (John 2:1-11) -- and at the foot of the Cross -- when Jesus concluded his passion (John 19:25) -- Mary is always in the background. Her presence is always pointing toward her Son. And that is the very heart of Marian devotion: a strong, omnipresent, and relatively silent expression of devotion to the will of God oriented to his and her Son.

Throughout the history of the Church, the saints have understood this truth. Two examples will suffice.

In the fourth century, St. Ambrose expressed the hope that all of his people would inculcate the spirit of Mary as a means to glorify God: "May the heart of Mary be in each Christian to proclaim the greatness of the Lord; may her spirit be in everyone to exult in God."

Similarly, 1,400 years later St. John Bosco had a vision of two pillars anchoring the bark of Peter in the midst of a stormy sea: the pillar of the Eucharist and the pillar of the Blessed Virgin Mary. The larger pillar, that of the Eucharist, had the words "Salvation of Believers," and the smaller, that of Mary, "Help of Christians."

Mary is, indeed, the help of Christians, leading them to Jesus and the Eucharist. Devotion to Our Lady is always together with devotion to Our Lord, especially in the Eucharist, as the Church sings: "Ave verum corpus natum de Maria Virgine …"